Panelists:

Laura Thomson / Director of Engineering / Mozilla

Miriam Aguirre / VP of Engineering / Skillz

Rija Javed / Senior Director of Engineering / Wealthfront

Vidya Setlur / NLP Manager / Tableau

Transcript

Laura Thomson: Hello, everyone, and welcome to the panel on engineering leadership from cat herder to air traffic controller. My name is Laura Thomson, and I’ll be your moderator. I’m going to begin by introducing the panel, and if each person could wave or tell us who they are as we go around, that would be great. First up we have Miriam Aguirre, who is the VP of Engineering at Skillz. We also have Rija Javed, Senior Director of Engineering at Wealthfront. Vidya Setlur, a NLP Manager at Tableau. And my name is Laura Thomson, as I said, and I’m the Senior Director of Engineering Operations at Mozilla. Welcome to the panel, everyone. We’re going to try to do this in a conversational way. I think a good icebreaker question is for us each to talk about what our career path was. How did we get here? How did we end up in these roles? So who would like to kick us off? Miriam, maybe?

Miriam Aguirre: Sure, absolutely. I actually graduated from college in 1999, and immediately moved to Silicon Valley. I went to MIT and graduated with a computer science degree, and it seemed to be natural for me to move to Silicon Valley. I spent most of my career here in the Bay Area, big companies, small companies, from HPs to two or three people companies. As a software engineer primarily, made my way into architecture and then joined a startup where I felt like I finally had to break into management just because I wanted to drive more of the decisions on what products to work on and what teams to build and how to build those teams. I just felt kind of like there’s only so much I could contribute as an engineer, but there were a lot of decisions where I felt like I could make better decisions at the management level. So I carved my way into leadership at Skillz, now as an VP of Engineering here.

Laura Thomson: That’s great. What about you, Rija?

Rija Javed: I’m originally from Canada. I went to the University of Toronto, did undergrad and grad school there. And then similar to Miriam and, I think, a bunch of people that moved to the Bay Area, that being the hub of tech and software. I was at Zynga, which was a very interesting experience, given that it is a gaming industry, very famine and feast, I was there for about a year, and then this interesting opportunity from a company called Wealthfront came about. The engineering culture really spoke to me, and I joined the company when they were about 20 or so people, and then I recently left when we were about 200+ people. So I was able to contribute across various different areas, and just grew within that role from being an individual contributor to leading and managing that core business area for Wealthfront. And, yeah, met a lot of great people and learned a lot professionally.

Laura Thomson: That’s awesome. What about you, Vidya?

Vidya Setlur: Well, I am originally from India, and so I did my undergrad in India and came here for grad school. My background is in research, so I’ve been doing research and NLP and it’s natural language processing and graphics for more than 10 years. And most recently, an opportunity came up at Tableau where I could manage an engineering team in this space, so it’s just been a great opportunity to practice some of the technical expertise in this area as well as people management hand in hand.

Laura Thomson: That’s terrific. All right, I’ll tell you about myself. I’m originally from Australia, which you probably never would have guessed. When I started college in computer science, the web didn’t exist. And then I decided that that was what I wanted to do for a living, so that worked out well. In Australia I ran a consulting company, went to grad school, and about 11 years ago, I moved to the US and started working for a company that did consulting for startups, really like a lot of scalability stuff. I’ve done a lot open source work and written books and so on, and that’s how I ended up working there. And finally, about 10 and a half years ago I came to work for Mozilla, and I started as a senior engineer and worked my way up to where I am now, which has been a great ride. I wonder, often, how much longer I can go on, but it’s been fantastic.

Rija Javed: Nice.

Laura Thomson: Okay, so next question I have is what’s your management philosophy? How do you approach managing up, dealing with your people that you report to, and down, which is sort of an expression I hate, actually, but, you know, the people you manage. Who would like to tackle it?

Vidya Setlur: I can. I’ll start off. My general philosophy and just watching people that I admire is leading by example. I find it highly uncomfortable asking my team what to do, but intrinsically motivating the team and inspiring the team to really feel the passion and being part of this journey and working on items. I can take the horse to the water and force it to drink, but there’s something lovely about someone who is just excited and passionate about working on certain projects. But, you know, by me getting in and working and leading by example, that’s for me, one way of getting people excited and passionate. The second aspect is just being a really good listener, listening to what people are saying, listening to their signals. There’s a lot of implicit listening that I like to do, their body language, their gestures … Are they uncomfortable? Does their voice need to be heard? So really acutely signaled into some of that as part of the way that I approach leadership.

Laura Thomson: That’s a wonderful answer. I really like that part of it, being a good listener. That’s really important.

Rija Javed: I guess my experience, the way I envision it, for in terms of people managing to me, I very much believe that a job of a manager is to make the people successful, and that’s not while they’re within this particular team or within this particular company. And the way I always look at opportunities, especially within the company scope, is what are the company’s priorities? What are the person’s skills, and what are their interests? And you always want it to be a step up for them, while keeping all of those things intact. And in terms of people higher up than me, I very much believe that an individual’s job is there to make the company successful, all the while, especially when you have people reporting to you, making them successful as well, too. But I feel like I myself have grown a lot within the companies that I’ve been at, and I think good things will just happen to you. You’re then able to make that impact, and other people will see the value that you bring to the table, and it will all work out professionally for you. But, yeah, for me it’s very much making sure that that individual is successful throughout their career and maintaining those relationships and having a good communication system.

Miriam Aguirre: Yeah, really understanding where people want to go and helping them get there and doing the right amount of pushing versus not. Listening, but also listening for things that they’re not saying, and digging in and asking those questions, and trying to steer them towards where they think that they want to go, and giving them those opportunities to see what that’s like. A lot of times you know, or you feel like, something will not be a good idea, or it may not necessarily turn out the way that they think, but you want to be supportive, and you want to give them that space to grow and find out for themselves what they want to accomplish. You taking on that support role is super important for me, in terms of management, just making sure that you’re being supportive but also pushing. I keep pushing them forward.

Laura Thomson: Right, I hear a lot of common things and things that I try to do as well, but maybe not as eloquently stated. A couple of things I really like to do … I like to meet people where they are and not try to force everybody to work the same way or follow the way that I think they should work. As long as they are doing good work, then it doesn’t really matter how they do it. I try to give people the freedom to be themselves. Also, really want to push responsibility to the edges. Wherever possible, the person who knows the most about the thing should be making the decision about the thing, and a lot of the time that’s not me. Those two things are really important.

The other thing is I try to encourage them. I take a philosophy of communication that is kind, direct, and prompt. Because I think, particularly in the open source world, you have a place where people can be kind of jerks, right? They’ll say, “Oh, my god, this code is terrible.” And sometimes you need to communicate that, but you don’t need to communicate it in that way. Also, you can go too far and be nice and not say anything, and that’s not helpful. What you have to do is be kind by telling them, by sharing that with them. Be direct. Say what you mean. And be prompt. Don’t think something and not get around to telling someone until it’s too late for them to do anything about it. That’s my philosophy.

Vidya Setlur: I think, adding to that point, is a fantastic book. I don’t know if you’ve read it. It’s called Radical Candor.

Laura Thomson: Oh, I’ve heard this is really good. I’ve not read it.

Vidya Setlur: It’s a very good book. It’s all about honesty and how you can care about people through honesty…

Rija Javed: I think … Sorry, one other point. One of the things that I recently read in a book … It was by Ray Dalio, and the quote there was that the job of manager and especially any person in a senior leadership role is to figure out the individual’s motivations and ensure that those align with the company strategy and goals. If you’re able to do that, then you’ll really be able to help the people grow, which are the most important part of any organization, and that will help the company grow itself.

Laura Thomson: That’s really great. What do we have next? Oh, this is a great one. So what are your thoughts about mentorship or sponsorship? I’ll just qualify what I think the difference between those are. Mentorship, it tends to be helping someone grow or receiving advice. Sponsorship is more the act of helping someone in their career, like offering them stretch opportunities, helping them be seen, and so on. So how have mentors helped you, and how have you been a mentor to others now that you’re a leader?

Miriam Aguirre: I’d like to hit on that one. I definitely feel like, as someone who has now spent a better part of two decades in tech, being really mindful of where I spend my energy. And especially when I think about giving back to the community, whom I choose to mentor and whom I choose to sponsor. I can only sponsor people who work at my company effectively, but who I choose to mentor, it could be outside of my organization, and that’s where I feel like I could make a big difference if I help girls in junior high or people of color before they leave STEM. And so I try to focus my energies around that.

In terms of my own mentorship and allyship, I try to be pretty focused about what I need from certain people. I have a senior executive that I consult with at Lyft, and I ask him for information that would not be readily available to me. For example, what would a white male ask for in terms of salary for this kind of position at this stage company? And him having that experience is able to give me that information pretty easily, and I don’t have to feel like without this information I can’t negotiate effectively. So being really specific and intentional about the info that you want or the kind of sponsorship or mentorship that you need really helps guide me and focus my energy.

Rija Javed: I like to echo that point, especially in terms of mentorship for outside communities. When I was in high school, in terms of my maths and sciences classes, it was actually most of the girls or women there that were actually achieving the highest grades. But careers, in terms of the STEM category, is just things that they would not think of, so they would try to go into more of a business side of things, whereas it would be more of the male population that would think about going into it. And to be honest, I actually first was doing undergrad in terms of business and economics, and then I just loved math way too much. So since high school up till now, for the past 10 years, I’ve tried to focus a lot more in terms of those diverse groups that wouldn’t necessarily automatically be thinking about the STEM careers, just to open up their mind to learn more about it.

Rija Javed: And then in terms of mentorship within the industry and within the company that you’re working with, I think it takes on lots of different forms. There are, of course, more specific relationships like onboarding mentor relationships, but there’s also a lot of stuff that you learn more implicitly from people. And I feel like I’ve really benefited in terms of that. While people may not necessarily be doing it, but you find them to be inspirational people, and that’s how I carve out my career journey. I think about it. It’s like those are the traits or those are the experiences that I would like to have.

Rija Javed: I think in terms of sponsorship, I read a great article, which I think is probably one to two years old now on Medium. But that was talking about how mentorship is not the answer for why women leave tech. The answer is actually advocacy at the higher exec levels. And that’s actually one of the things that I’ve been more mindful of, given the leverage that I’ve had at the company and thinking more about that diverse group and how I’m able to speak up for them. Because I also know that I’ve been able to grow in my career because there’s been that one person for me that’s been speaking up for me at that high level E-staff and board level.

Laura Thomson: I really like what you said about the implicit mentorship. I always think you should watch what people do, and if there’s something they do that’s great, ask them how they do it and steal it. Make it your own so you can … It doesn’t have to be a Yoda-style relationship where they guide every action, and you’re running through the jungle and learning all these things in this really hard way.

Rija Javed: Yeah, exactly.

Vidya Setlur: And I think that also dovetails into the previous point I made about being a good listener, but also being a really good observer. Because what I’ve realized is the best advice I have given as a mentor or have been given from a mentor is stuff that just happens implicitly without any sort of descriptive advice. I’m not saying that there is no place for that, but sometimes watching situational awareness and how people react in various situations is a really great way of observing and learning and recalibrating ourselves as individuals. I think for all of us here on this panel, we have the responsibility of mentoring the upcoming generation and our peers as well as continuously observing and learning from other people that we look up to.

Vidya Setlur: And the sponsorship thing is really good. Both Rija and Miriam raise some interesting points on, yes, you always want to have someone who can advocate for you or advocate for certain values in place in addition to someone intrinsically motivated and mentoring and helping you grow as a career. And you need both, and there’re places for both in a company and situation.

Laura Thomson: I think that’s really true. Sponsorship is sometimes an easier model, too. And I saw that as a question that I’m not going to answer it particularly or directly about finding people to mentor you at the mid and senior levels, and sometimes sponsorship is a better model there. It’s okay to approach somebody and say would you sponsor me, but I think you need to figure out what you want to get out of it first and make sure that you identify somebody that has the skills or is in the position to help you. And be prepared for them to say no. But I think one thing you can also in those situations is if somebody says no, say, “Well, can you suggest somebody else that might be able to help?” So don’t be frightened to ask. The worst you can get is no.

Laura Thomson: Okay, I did want to mention there are a bunch of questions coming up. We’re going to do a few more questions that we prepared earlier, and then we’ll switch to doing questions from the group. So if you haven’t had a chance, if you’re in the audience, look at the Ask a Question section, vote up questions that are interesting, write your own while we’re talking, and we’ll look at them in a few minutes.

Laura Thomson: Next one I have… let’s talk about challenges, challenges or failures that you have faced throughout your career. They could be things you overcame or things that you don’t think you handled particularly well. Let’s talk about those. Who would like to go first?

Rija Javed: I can start off. When I joined my prior company, the company size was 20, and I was the only female, let alone female within engineering, and certainly people who had five to 10 years more professional experience than me. So I really had to show my value in terms of the work that I was delivering. But one of the disconnects that was there for some time was you might be acting within a role and delivering that impact, but not necessarily getting the title that’s associated with it. And certainly situations where there were people with me that were not necessarily as diverse — they were white / male — and the treatment that they got versus the lack of audience that I got in that situation and the answer that I was literally told were like, “Well, yes, for this very powerful person, you don’t look like the people that he’s used to dealing with, and you just look very different to that.” And I think that prior article that I mentioned of why women leave tech, that Medium blog post …One of the things that it did mention was if … sometimes there are stereotypes associated with women.

So, if you are this very strong leader, then sometimes in conflicts that can be viewed negatively, whereas potentially a white male, who people are more used to, can get more claps on the back of, hey, you’re a strong leader, and you stood up for those ideals. Those are certainly some of the challenges that I’ve had to work through. There’s certainly technical challenges as well, and that’s a conversation that I was having with one of my peers, as well, is I think especially as you go higher and higher, it’s more so about cultural challenges that you have to deal with, and I certainly believe like no situation, no company is perfect, there’s going to be politics everywhere but it’s like what level of politics are you okay with and at what level does it really start to get super toxic?

Laura Thomson: Yep.

Miriam Aguirre: I think for me personally, when I think about my growth in tech, when I think about failures and challenges, what really stands out to me is how much time I feel like I’ve wasted fearing to fail as opposed to overcoming the actual failures. They’re not that remarkable now that I think about all of those failures and some of them I can’t even remember but there’s been plenty of failure throughout my career. What I feel most bad about isn’t those failures themselves, it’s actually how much time it took for me to make those decisions and not be okay with taking that risk and that’s really what I would like to change, not the failure itself. I think failure is just part of our roles, part of our jobs. We have to be able to manage through that. It’s really the lack of decision making that I feel bad about personally. When I think about how I approach my work now, it’s not out of a place of fear, and definitely like I know how to get through failure, I’ve done it plenty of times now. It’s more like let’s be decisive, let’s make good decisions, and let’s do it quickly without wasting time around being afraid.

Laura Thomson: That’s a good one.

Vidya Setlur: Yeah, I think for me, I think the general thread of thinking whether you classified failure as challenges, that’s to be discussed, but I think this is just sort of reminiscent of women in tech who tend to overcompensate for the role that we have and you just talked about that too. I found that starting from grad school because I chose to have a kid in grad school and as it is being a woman in a computer science department pursuing a PhD has its own bias feed and that on top having a child leads to all sorts of assumptions and opinions that people, especially men tend to have, “Are you really cut out for grad school? Is this what you want to do?” Comments like, “I guess I’m not going to see you once you have your kid.” I think for me, the way to address those challenges has been to just overcompensate. Working really hard as a grad student, not playing video games like my male peers, right? Because you feel like you’re constantly judged based on what you’re doing and I think it’s a common thread for me as I have grown professionally. I mean Tableau has been a great company but just because I have been trained and sensitized to overcompensating, I realized that we all wear so many hats that are beyond our pay grade or job requirements and we just do it. I have seen guys saying, “You know what? You’re asking me to do this, you need to give me a salary hike,” but we dare not ask such a question, right? We just do it and we sort of underplay or downplay that overcompensation that we’re doing because we feel that we need to prove ourselves beyond this stereotype that is often there. To me, part of the undercurrent of challenges that I face and I feel that a lot of people can kind of relate to that as well.

Laura Thomson: That’s a good one. I know for myself, one of the biggest challenges I’ve had through my whole career is I have really bad imposter syndrome and I’m sure I’m going to learn that probably like 99% of the people on the call have this to some extent but it’s really frustrating. Like you sort of feel like you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t. I have this thing that I want to work on, if I talk about it people will think I’m an idiot, is it really a good idea? If we do it, what if I fail and I’ll look stupid and all this kind of stuff. Like it was a very strong problem for me.

One of the things that’s helped me a little bit with that is realizing that it applies in every aspect of my life. I’m also a parent and when I became a parent, I said, “I have no idea what I’m doing, but all of these other moms know what they’re doing.” I was like, “This is imposter syndrome again, I just can’t get rid of it.” It’s kind of good to know that’s just how my brain is. That actually helped me a lot with the career stuff, was it was like, “Okay, this is how it works, I just have to ignore it.” It’s super helpful.

Vidya Setlur: Yes.

Laura Thomson: What do we have next on the list? Okay, so what do you do, each of you, to develop and hone your leadership skills?

Miriam Aguirre: Sure, I’ve got a couple of networking groups. I participate in an engineering Slack group as well. I like to, on my very long commute, I listen to podcasts or catch up on blogs and kind of follow different leaders in engineering and just kind of catch up on articles and keep in touch with the community. I find that kind of research really helps me keep abreast on what other people are doing, what other companies are doing and if they’ve solved some problem that either we are facing or we’re about to face and I don’t even know it yet. I can stay ahead of that stuff and kind of really reach out and kind of get more information around like how they approach the problem and how they came to those solutions because even having the framework for solving those kinds of problems is really valuable even if the problem isn’t directly applicable. I like to read up on the industry and also leaders that I feel are really good leaders at really good companies and try and model after them.

Rija Javed: Yeah.

Vidya Setlur: Yeah, for me, I definitely lean towards honing my technical aspect of leadership. I found that in a meeting, if I’m having a conversation tying it back to something that’s technically grounded often helps me in my role because of the nature of the team that I’m leading. Since I came from research, I continue to be very active in the academic community. I publish at conferences. I do peer reviews with papers. I also, the Bay Area has a lot of opportunities to mingle because there’s so many meet ups on various technical issues, also kind of women in tech issues, so just socializing and being out there and listening and learning and just being actively learning and growing is something that I continue doing.

Laura Thomson: Yeah.

Rija Javed: I mean, I don’t necessarily do as much reading. I try to keep up with some of the stuff but for me, the value that I really place on is on the individual themselves, so I have this collection of people, not necessarily engineers themselves, but within the tech community and some a little bit outside that I very much respect. When it comes to some like high-level decision-making process that I’m going through, I tend to look at a lot of the metrics, like try to be data-driven, but then I also place a high value on the opinion and advice of those folks, and also try to — which I think kind of echos what Vidya and Miriam mentioned as well too — try to learn from the people around me and that doesn’t necessarily need to be like the people that are laterally above you, but people that are around you or below you because everybody has a different way of doing things, and you might be able to learn something from that.

Laura Thomson: Yeah. Yeah, and I think that’s not just learning what to do but sometimes you can learn things that you don’t want to do, right? We just started saying about work too, I mean reading blogs and whatever but I hope it will all work out but one of my awesome colleagues, Selena Deckelman has just started Management Book Club and when I was talking about this when we were preparing, someone said, “Did you actually read the book?” I think it was Miriam and it’s really well-structured for managers because it’s like a chapter at a time so you know, we’ll meet to discuss chapter four. That’s okay, I think everybody can commit to reading like a chapter. I’m hoping that works out really well, but I think the conversation is about it with the other leaders is probably even more important than reading the book.

Vidya Setlur: Laura, what’s the name of the book again?

Laura Thomson: We’re going to do different books, I can put a link to the one we’re doing first. Ask me again in six months if we kept it up. That would be a good question, but I really like the idea. Okay.

Tell me about a bright spot in your career. What was something that you think of as a highlight or a high point, something that went really well.

Miriam Aguirre: I’ve been pretty pleased the way we’ve approached hiring at Skillz and kind of some of the resulting stats from that. Deep down, everyone believes that diverse teams help a company perform better. I wanted to actually apply that and have some results come of it. When we were named the fastest growing company revenue-wise for Inc. 500, I was like, “This is exactly like the proof that people want to see, right?” Sometimes people do things the right way because it’s the right thing to do. Sometimes they want to see that the numbers look good and this is kind of a sweet spot where I feel pretty happy that we’ve got both those things and really want to share that success with other leaders and kind of help them achieve that same level of success because I do feel like at the end of the day, the diverse team really does help the company build a better product and if you’re in a business that wants to make money, that’s very important and you can’t overlook that. It costs money to overlook that.

Laura Thomson: Yep, that’s a great story.

Rija Javed: I think for me, the highlight of my career and the best project that I worked on, which has also been the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do was, I was managing that core business area for Wealthfront so we were trying to scale the existing platform but we also wanted to remove some of the middlemen that are associated with the brokerage and financial industry so re-architecting that whole platform and taking all that responsibility in-house, which was a massive undertaking but we didn’t also shut shop so we’re still delivering the new client facing features on top. We also went through like a massive hiring endeavor too as well with somewhere around like 40 or so people just within like a three to four-month span.

That six month period in terms of onboarding, that was like a net negative and a very painful experience for me, but I truly also believe that people are the most important part of any aspect so once they were fully onboarded, and this endeavor — I call it a project but it was a two and half-year endeavor — and it just kind of like really opened up the gates for my company in terms of the products and the areas in which we wanted to expand and also just the control we should take in-house. Then we decided to build while this was going on, a new client facing feature on top, which we knew nothing about and the timeline was compressed on us because our board financing the decision but because I had a great team. There were a lot of tough challenges both technical and to be honest, cultural as well too because we were working with 30 different vendors and hiring people from traditional industry who were just not used to tech at all, so for me to be able to kind of like onboard them and work with the different mental models, certainly the hardest thing that I’ve had to do but also probably the proudest thing because I was just humbled to have worked on it, let alone be able to lead and manage that whole thing of 80+ people, certainly something I’m proud of and a highlight.

Laura Thomson: That’s amazing.

Rija Javed: Thank you.

Vidya Setlur: When I joined Tableau almost six years ago, it was nothing about natural language. Tableau had been an analytics platform supporting visual analytics and I joined a research team but people would look at me oddly and say, “Oh, you have an NLP background, but I guess you also have a graphics background so it makes sense that you’re in Tableau.” I think what I’m particularly proud about is working on the research team on a bunch of prototypes, which focus on the research team, primarily women, I must say, and there was a precipitation point where it’s almost like you have to be at the right time at the right place, the stars need to align for a company to really buy into a research idea. It’s a multi-factor optimization. It goes with competitive landscape has to be just right, the idea has to be well thought through. It needs to excite the decision-makers in the company. It needs to make sense to the company’s business because there’s so much beyond just a good idea and we presented a particular prototype to the executive board where they got so excited that they started a seed engineering team with a female engineer, actually, and then Tableau acquired a start up and now NLP is a first class citizen at Tableau. Everybody talks about NLP. So it’s just exciting to see that technical shift and kind of the respect and the whole ecosystem that comes with that. You have sales people passionate about it talking to Tableau customers. There’s a whole body of work in the research community that’s looking at NLP with visual analytics. It’s just been remarkable and I would just say it’s been lucky I’ve just had a lot of good people working with me and just some good luck as well.

Laura Thomson: Yep. That’s amazing. For me, I think the thing I’m proudest of over the last couple years is actually more of a cultural change than anything. There’s a lot of technical change but mostly a cultural change and the program we have that I came up with, which is called, rather unglamorously, Go Faster.

I come from a web development background and when I moved to actually start working on Firefox, I said, “Why do we only ship every six weeks? Why don’t we just deploy this continuously?” I think I upset a lot of people by saying that. The nice thing about that is, I’ve always kind of thought with continuous deployment, the things that you do to promote that [inaudible 00:35:11] for your culture anyway. It means lots of tests, lots of sort of good data and experimentation and trying small incremental things and seeing if users like them and iterating quickly. We’ve historically been a risk averse culture, which might surprise you, and also a culture that is like allergic to collecting any kind of data because it’s sort of the clash point between Mozilla’s mission. We’ll respect user sovereignty but also try and deliver a good product. It’s like we’ve had to come up with sort of set of lean data practices so we can collect data about the product without invading anybody’s privacy to iterate quickly and make a good product. We can do that now. We can ship multiple times a day if we want to. We mostly don’t but we do a lot more experimental work. We do a lot more testing and experimental features and feature flagging and a lot of things that I am used to doing as a web dev. I feel really proud about that. I think it was sort of one of the key things that allowed us to ship Firefox Quantum last year, so it feels really good to have pulled that off and it kind of surprises me still.

Rija Javed: Nice.

Laura Thomson: It was fun.

Rija Javed: Yeah.

Laura Thomson: Okay, so I have one more question from our prepared ones then I’ll go to the audience questions. This last one I think is a really good one for this audience, which is what do you do to promote inclusive leadership and make people from diverse backgrounds feel welcome in your team? That includes intentionally including people that have a various sort of intersectional differences.

Rija Javed: I think, sorry, I can get started unless-

Laura Thomson: Yeah, go on.

Rija Javed: I think one of the things that I really try to focus on is like the different level of diversities. Like it’s not just, and a lot of companies tend to focus like oh race, gender, and now like maybe thinking about like say sexual orientation or socioeconomic background, but there’s also different personalities in that mix and one of the things that I have been very much cognizant of, especially in the last six to eight months, is some people are more outwardly and happy to speak up for themselves and also opportunities that they would want, which kind of works well within the startup’s culture, as well too, where you almost don’t have like a whole lot of hierarchies associated. Other people are just as impressive, they’re just more behind the scenes and not necessarily super comfortable about even expressing their wants about which project they want to work on and what opportunities they’re next looking for.

One of the things I’ve been cognizant of like trying to really assess the team that I have in terms of, like it’s that whole ecosystem as opposed to the individuals associated with it, and how they’re kind of contributing and working together. First off, as soon as I start mentoring or managing somebody, it’s trying to figure out what their motivations are to like really grow, like why are they even an engineer? Not just working within in this team or within this company but what they want to achieve? Then within that set of how they compliment each other’s skills and the opportunities that are available, try to kind of give them those prodding or those opportunities even if maybe it’s like, “Oh, Julia, you had this great idea, or Bob did this thing over the weekend that actually was great results, or as somebody else mentioned this article.” Yeah, it’s not necessarily super concrete because I think it just depends on the team that you’re working with.

Laura Thomson: Yep. Great.

Vidya Setlur: I would just say just responding to that, I love the word ecosystem and for me, it feeds into kind of a broader philosophy that I have for my team that everybody needs to be in this [inaudible 00:38:44] mindset as opposed to a fixed mindset. In order to achieve that active learning mindset and growing from other people on the team, you need people from different backgrounds, the typical ones that we often see but also more nuanced as we just said. Introverts, extroverts, different skills.

If I have a team that is all highly-functional with superstars and all senior engineers and no junior engineers, people can get cocky. They’re like, “No, we all know what we’re doing,” and there are no opportunities for mentoring and helping junior engineers or even interns [inaudible 00:39:30] and at the same time, interns or junior folks have an opportunity to be mentored and learn and ask the right questions of more senior people. You can slice and dice these across different types of diversities, right, but at the end of the day, you have a puzzle, they’re not all going to fit perfectly. I mean there are going to be bumps, that’s how we are as humans. It’s not perfect, but in that process, you learn, right? Everybody learns and constantly recalibrates and figures out, what can we do to make this situation better?

Laura Thomson: That’s great.

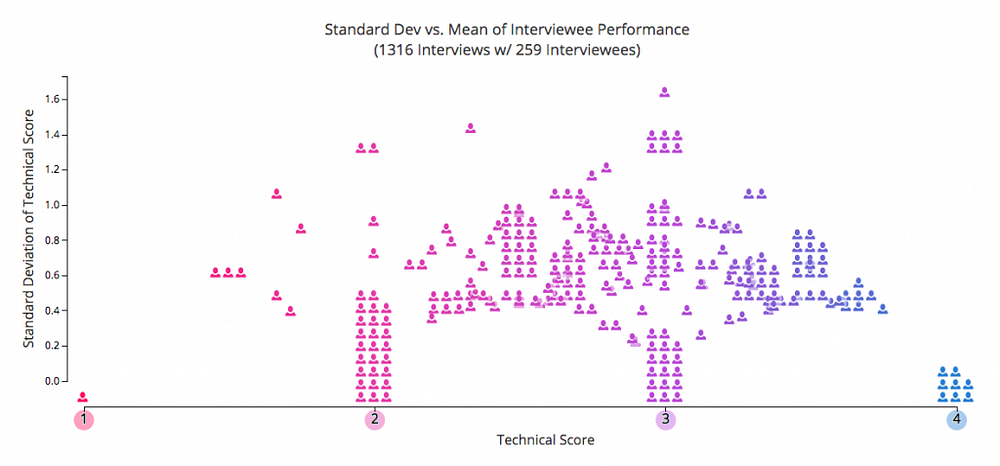

Miriam Aguirre: I feel like this is one of those things that if you start out with a non diverse team it gets harder, and harder to fix that problem. But if you start with a very diverse team it lends itself very well to continuing to promote diversity; from the hiring decisions, the recruiting, how it’s done, how we present ourselves. But very hard to fix later on. You can start by doing the right thing, and things will be kind of steady state and not that hard to fix later on, or you can be in a situation where you’re like a Google or a company like that, where you just have a ton of work to do there. I think for us, because we’re in this situation where what we’re trying to do is to continue to promote that. We’re more open to different backgrounds, we’ve got objective testing that can help us suss out whether or not you’ve got the technical skills to succeed here and we don’t really look at that CS degree as a bar that that’s the first barrier to entry.

We feel good about processes downstream being able to inform us whether or not we think the person is going to be successful on the team. Then once they do join the team we make it part of multiple peoples goals to have that person succeed here at the company; so it isn’t just that individual out there floating by themselves. Multiple people are responsible for the success of that person; and they know it and everyone is aware of, okay you’re this person’s tech lead, you’re this person’s mentor, you’re this person’s … All of those pieces of the onboarding that we try to ensure that once they’ve joined the organization they’re going to have the support framework to succeed here. That really helps us, all of us, be invested in the success of any one individual; just at the end of the day just fixing hiring isn’t going to fix the other problems.

Laura Thomson: I want to pick up on one thing you said that I absolutely agree with you that it’s so much easier to have an inclusive environment if you do that from day one, right? To use a terrible engineering analogy you don’t build the product and then try to tack on security with duct tape, because you’re doomed to failure. It’s so much easier to start from a diverse, inclusive place and just build on that. I suppose it can be done, but it’s always going to be an uphill battle. For us, I really want people to be able to bring their whole selves to work. A couple of things I try to do to help with that are to talk about like, this is a really really basic example, you know if I am sick, or I’m taking time off because I need to do a parenting thing or whatever, I tell people about that. I know some people might feel like they have to hide that they have to take time off work because they have children or whatever. They can feel embarrassed, like oh I’m a mom and therefore I’m unreliable, blah, blah, blah. I always say, I’ve got to take off early today because of this child-related thing, because I want other people to be able to be free to do that. I talk about it because it’s a way of sort of making it clear that that’s okay. Using the privileged position that I have to establish that that’s a good baseline.

There’s just more basic things, like making sure quieter people get heard in meetings and not having every team building be about drinking beer and riding ATVs, and all sorts of … There’s lots of really basic everyday things. I’ve learned a heck of a lot from our head of D&I Larissa Shapiro was on this call and she’s awesome — so can’t say enough good things about her, how lucky we are to have her working with us. I am going to jump to the audience questions. Top of the list is, how do you find mid to senior career mentors? I feel like every time I look at a mentoring group they only want me to be a mentor, which I’m happy to do, but I want both.

Rija Javed: The approach that I’ve taken is just kind of really seek out, and to be honest, kind of like grab the opportunities and just go and ask the people myself. I try to … I like my prior opportunity just because I think it truly attracted top talent from various … Not just within engineering, but seeing the people that I respect, who have delivered and are able to inspire people. Not just given the past work, and what it says on their CV, and on LinkedIn, but the value that they’re delivering right now and you’re able to see. Then just kind of literally go and seek out those relationships. Be like, hey would you mind going on a coffee, or whatever. What I’ve actually found is people are more than happy to provide that mentorship and that advice to you. I’ve had the reverse happen to me as well too, but I’ve seen that people have been shy about it, so I’ve literally kind of taken them out and then once you’re there, then a whole bunch of both hypothetical and actual, real practical life questions come out that they just want your advice and feedback on.

Laura Thomson: That’s great. Anyone else on that?

Vidya Setlur: I would add that at least a couple ways one could possibly find these mentors is, what I found helpful is finding a mentor that would sustain a long term relationship. When I started as fresh out of grad school I had a mentor and both of us have sort of grown professionally over time. There’s still an interesting relationship in terms of the types of experiences that person can relate back to me, as well as growing in my professional career and exchanging notes. That relationship has changed over time, but it’s sustained because the underlying theme is trust and context. I don’t have to give my whole dump of where I am every single time, because it’s sustained. I would say those type of mentors can be rare, because we move, and switch companies, or people get busy, so things happen that way.

Another piece that I have found useful is, especially for people like us in senior levels, we probably have changed companies a few times, or changed management lines a few times. I have found, personally, that some of the best mentors that I’ve come across have been people who were my managers in the past, maybe at a different company, or in a different line, who I have respected, trusted, but because they are not my manager anymore there is a different type of relationship where they can be more mentors. Mentoring as opposed to managing. There’s a lovely reflection there that happens. Kind of seeking out into your network and finding those [inaudible 00:47:28] examples of people that you’ve worked closely with, or that managed you, whether that be directly or indirectly, and seeing if they can help mentor you in your next path, or next endeavor.

Miriam Aguirre: I would reach out to executives, especially if you want to meet someone at that executive level. It doesn’t necessarily need to be a person in your company’s executive team, but they will probably know other executives and can maybe recommend someone. If you’re specific enough about what you’re looking for, what problems you’re looking to solve, or what kind of mentorship you need, I feel like reaching out to your execs, or having them reach out to their board is not out of line for this kind of mentorship. A lot of people are very interested in sharing that women in tech stay in tech. I think that expanding your search and having other people who are already in those positions help you with that search can also be beneficial.

Laura Thomson: That’s great. Okay. I don’t I have much to add, so we’ll go to the next question. If know you’ve undervalued yourself in terms of salary how do you approach your manager to correct it so you’re paid fairly on par with your peers?

Rija Javed: I think the way to look at it is more objectively. I think companies, especially startups, kind of go through various different phases of that, but hopefully there’s some sort of engineering, or within whichever function, some levels associated it. Which is like, hey this is the roles and responsibilities that come with it, and that there’s advance associated with that level in terms of the compensation and various different rewards that go with it. I think having a very open and honest conversation in terms of the value that you are delivering; both objectively in terms of what you’ve delivered in the past, and making sure that you are prescribing and delivering on that particular metric, and hopefully by going through that feedback assessment, or whatever feedback loop that you have, your peers both within engineering and depending on the level that you’re in you’re probably working cross-functionally with folks as well too that can kind of really attest to that in a way.

The worst way you could potentially go about it is the compare and contrast approach, which as human beings, however much you try both preach and try to do, it’s just really hard to get out of. It’s like, oh hey I’m doing this, but this other person is doing that, and I think that’s how much their level, or title, or what they’re actually being paid is. I’ve seen both, me myself potentially being in that situation, or somebody having that conversation with me. Compare and contrast is usually, I think, the bad way to go about it. You want to look at it more objectively in the value that you yourself are bringing.

Laura Thomson: That’s great. One thing I would recommend is go with data. If you can collect any data points, and also it’s really good to rehearse any kind of those awkward conversations where you’re asking for more money, or you’re asking for a promotion. Rehearse it, practice it on a friend, a coworker, a spouse, whatever, so that when you actually go to have the awkward conversation with your boss … Because none of us like to talk about these things, it’s uncomfortable, but it’s like giving a talk; if you’ve done it before it will be easier.

Miriam Aguirre: Yeah, actually I feel like if your friend is up for it, they would really do you a favor by saying no and then that way you get that shock out of your system and you don’t freeze, because that is a potential outcome of this conversation. If you can practice that no with a friend, have your points, and your follow ups ready to go I think that will go much smoother when negotiating in person. I definitely agree with that practice the negotiation in advance.

Vidya Setlur: Yeah, just adding to that. Getting a friend who can play devil’s advocate is good.

Laura Thomson: Yeah, and never work for somebody like that. But yeah, absolutely. I think it’s really important. One of the things that I have done, more on the asking for a promotion than asking for a salary, is to say, what’s the gap? If you’ve said no, what do I have to change? What are the things that you need to see from me in order for me to get this and will you help me work on those things? Make them invested in your success, because it’s their success too.

Rija Javed: Yeah.

Laura Thomson: The next two-

Vidya Setlur: We complete goals, right? What is the delta? This is what you’re expecting of a promotion and just articulating the action of the item. That’s also useful as being a manager of individuals on a team. When you give them feedback and helping them identify learning opportunities, coming up with concrete actions that [inaudible 00:52:09]. Obviously to have data, have points of view that are more concrete.

Laura Thomson: That’s great. Okay, the next two questions are related. I’m going to read them both and then people can tackle whichever part of them they want. The next one is I’d love to get more details on the managing up questions from the panel. The second one is, leadership has two roles, managing those in the organization, but also managing and leading up. As leaders in tech, what advice can you offer for influencing company values to be more inclusive towards diversity, and other values that are meaningful to employees who aren’t white men, especially when there might be resistance to that.

Rija Javed: In terms of just managing up, one of the philosophies that has been one of my go to things and that I actually tell people within my team to do as well too, is over communicate versus less. If you think this information might be useful, even if you don’t think it is. I have literally kind of like — we used to use HipChat as opposed to Slack — but like literally spent selling spam messages almost, I like to call them, just because you don’t know what their filter might be and you always want the information to be going up as opposed to, like I had this one odd case. I was on vacation and got a text later on at night because of it, where the information because of the cross functional group went all the way up, down, and then… It was just this weird thing where you always want it to be going up. And to one of Vidya’s points much earlier, which was in terms of what your leadership skills are, I think both over communicating versus less, because people as you start to go higher up, they tend to lose context.

Maybe this is a bad example given the current tech world that we are in, but people love information, right? That is power. As leaders, you also want to be leading from the front. Having that social capital, and that social equity of the people that you are actually leading, because you are actually able to deliver, or have delivered in the past as well, and you know what you’re talking about. Then that’s also going to speak volumes at the higher up levels, because you have that social capital to back you, as opposed to just this potential — as organizations sometimes scale there’s this different perception; the upwards and the downward perception, and you want to keep that consistent. If you’re able to deliver, then the team itself is going to be kind of speaking for you, and the higher ups are going to believe more of what you say versus like no this is more of a middle manager, and maybe the team is feeling differently.

Vidya Setlur: I think for me there is a certain craft in terms of … kind of going back the point that communication is really important. I think there is a certain craft that comes with communication depending on whom you’re talking to, whether it’s managing up or down. For instance, there needs to be a way for me to articulate what our team is doing, or what it’s focusing on, and the customer value in a way that folks above me can either understand, or be active, but given communication that comes from upstream, downstream, or the way I need to communicate it with my team, you have to be more nuanced, or filtered, or updated based on how people are going to perceive that communication. I think getting more skills in terms of how one crafts communication, and the nuances of that based on who the target audience is, is definitely something that helps someone grow as a leader.

Laura Thomson: We are getting low on time. I think we can try to do these next two questions, because they’re both, I think, really quick to answer, then we’ll wrap up.

The next question is how many of you are still coding on a regular basis while being managers. I’m going to go first, which is I don’t code at work. I don’t code for work because it’s not my main job and I would just be blocking somebody else from getting something done. When I code these days it is like on a side project — on a plane is a great time to be writing code, I spend a lot of time on planes, that’s awesome — but yeah, I don’t want to be on the critical part for anything, because that’s a huge mistake in my mind. Anyone else?

Miriam Aguirre: Same for me. I don’t actually code anymore. I do on occasion peek into pull requests, and drop in some comments, but no, they don’t let me check into the repos anymore.

Rija Javed: Yeah, I’m on a similar path as well, too.

Vidya Setlur: I actually actively code.

Laura Thomson: Yeah, that’s fine.

Vidya Setlur: I review code, I write code, I look at the engineers. Yeah, I figure out which projects I work on… For me, being technically hands on is important.

Laura Thomson: Yeah, for me I think the crossover point is somewhere between being a line manager, and a manager of managers. About when you become a manager of managers it stops being a good idea. Anyway. One other question, I noticed all of you went to grad school, do you feel it made it easier for you to become a director or VP, or that it’s necessary to become one. I’ll start by pointing out I dropped out of grad school as is quite traditional in this industry. You don’t need it.

Miriam Aguirre: I didn’t go. Yeah, I didn’t go to grad school.

Rija Javed: I didn’t find it useful.

Vidya Setlur: I found it useful, especially with something as specialized as NLP. I’m kind of the black sheep.

Laura Thomson: Yeah. I think there are exceptions to that. If you want to be in research, if you want to be in data science, it doesn’t hurt. I’m sure there’s other things where it’s obvious, but it’s never going to stop you from getting a job, I think, at the end of the day, not at this point in our industry anyway. Okay, any last words? Anyone have anything else that they want to add that I should’ve asked? We have one minute.

Vidya Setlur: I should just say the questions that were coming in, I’ve been watching them, I’ve been really awesome.

Laura Thomson: They were great questions, yeah.

Vidya Setlur: Thanks very much and I hope the audience found this useful.

Laura Thomson: Thank you all for coming today. I had a lot of fun. I hope you did too. Thanks.

Miriam Aguirre: Thank you.

Rija Javed: Yeah. Bye.