Transcript of Elevate 2020 Session

Sukrutha Bhadouria: All right. Thank you. Next up is Alekhya Pochiraju. She is a biomarker operations manager at Genentech, where she provides clinical oncology biomarker operations expertise. She believes biomarkers are a critical element of cancer drug development and cancer therapeutics. Alekhya will share with us today how non-Caucasian and underserved populations must be appropriately represented in clinical trials in order to ensure the efficacy of treatments across the board, across all populations. And before Alekhya gets started, I want to just remind everyone that this is definitely recorded. You’ll be able to watch all the talks on our YouTube channel, youtube.com/girlgeekx. And please tweet photos and posts on social media, any tidbits that you feel like you’re learning that you want to share with everybody else, with the hashtag GirlGeekX. So, thank you Alekhya. I want to make sure we thank you for the time you’re spending today. Go ahead and get started.

Alekhya Pochiraju: Hi, Sukrutha. Hi everyone. I’m Alekhya Pochiraju, from Genentech. And I’m excited to share my perspective on importance of diversity within clinical trials. This topic is near and dear to me, and I truly believe it is the best path forward in providing the highest standard of care for all populations, with emphasis on all populations, not just a specific segment of the population. Before we take a deeper dive into why diversity in clinical trials matter, allow me to provide a high level overview on how we get medicines to the patients and the design process behind it. Like almost all good things in science discovery, it starts in the lab. And for the purpose of today, I’ll say the focus of clinical trials is to bring new and better medicines to patients.

Alekhya Pochiraju: After successful lab research, clinical trials begin in phase one, and it involves testing on a small number of human volunteers, for whom better alternate options are lacking. And the focus of phase one, is to understand the effects in humans, specifically the safety aspect of it. After phase one’s success, the trial can move into phase two with a larger volunteer number, to determine both safety and efficacy. Eventually, when the medicine enters into phase three, the purpose is to confirm the safety and the efficacy data that has been generated in both phase one and phase two. The phase four of the study takes place after the medicine has been in the regulatory approval, meaning after it has received FDA approval and it’s already on market. And the purpose is that it’s designed to collect broader efficacy and safety information.

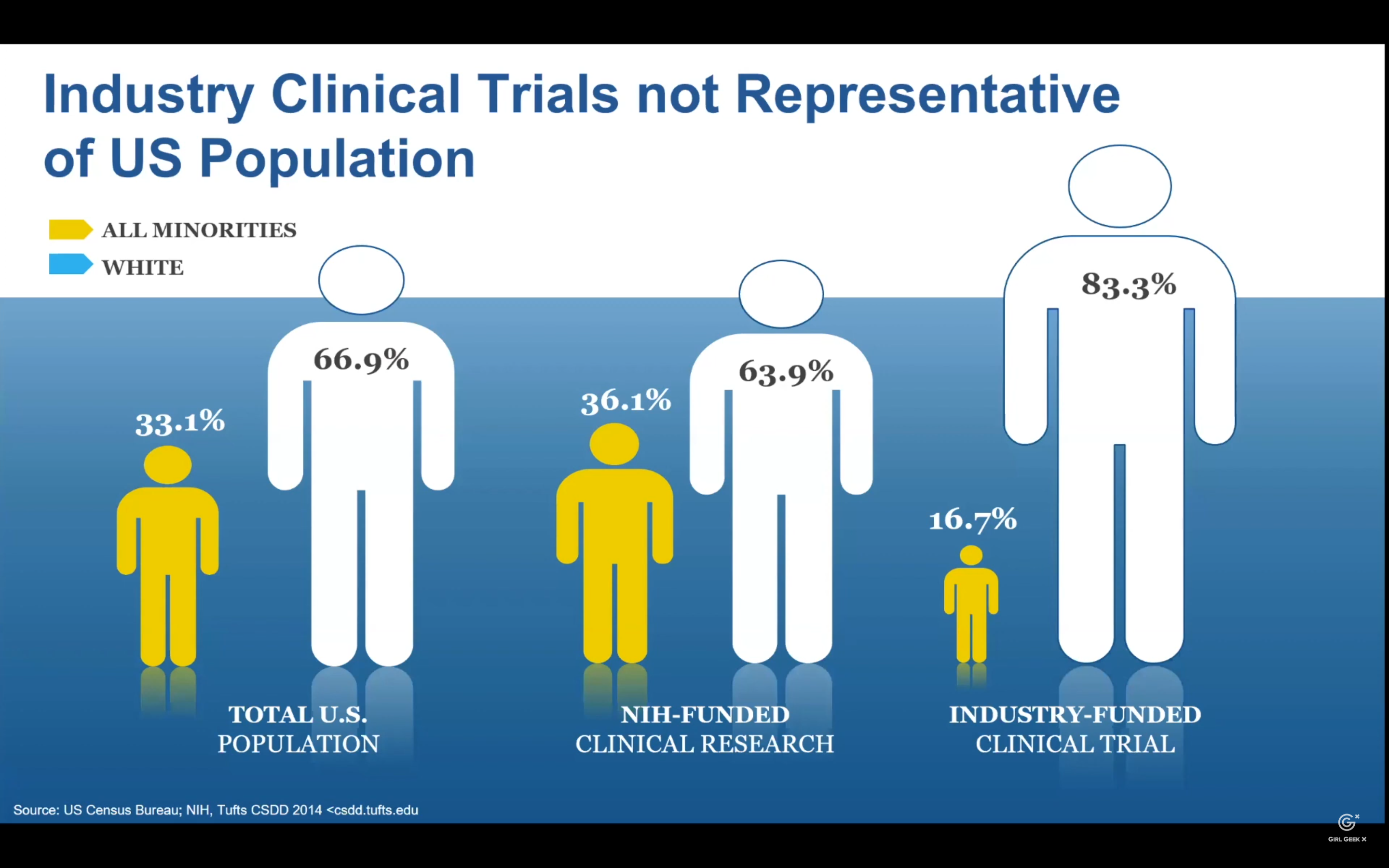

Alekhya Pochiraju: What I have here is a pictorial representation of US population and how it is represented in both federally-funded NIH trials (NIH stands for National Institute of Health) and industry-funded trials. How a patient responds to medicine can depend on different factors. Some of them would be genetic background, ethnicity, gender, and lifestyle. So, it’s important to have reliable representation in clinical trials. Unfortunately, minority populations have been both historically and consistently underrepresented in this clinical trial. As a result, the important information about how the medicine works in minority population is not always available. As an example, I would say US census data says African Americans should present 13% of US population. Yet, FDA reports that these populations constitute only 5% of clinical trial participants.

Alekhya Pochiraju: The disparity is even greater and, unfortunately, more in Hispanic and Latin origin communities. They represent 18% of the US population pie, but only 1% in the clinical trial participants. Because of this under-representation, we don’t know if all of today’s medicines are equally safe and effective for all populations. These disparities in representation magnify it has to be moving to the future. It’s estimated by 2045, most of what we now define as minority populations will be majority. It’s common knowledge that clinical trial process takes years, if not decades, from inception to a commercially available medicine.

Alekhya Pochiraju: What I’m trying to say is that the way the trials are conducted currently don’t represent the patients of the future. The advances in technology we have seen, there is significant increase in the usage of computational modeling and designing within the drug development process. Then, these models use publicly available genomic databases. It potentially amplifies the disparity. And the reason being that, 80% of the existing database is from European ancestry. This is also a challenge and a limitation as health industry is moving towards personalized medicine or precision medicine, which essentially means identifying treatments that work for an individual patient or a small cohort of patients.

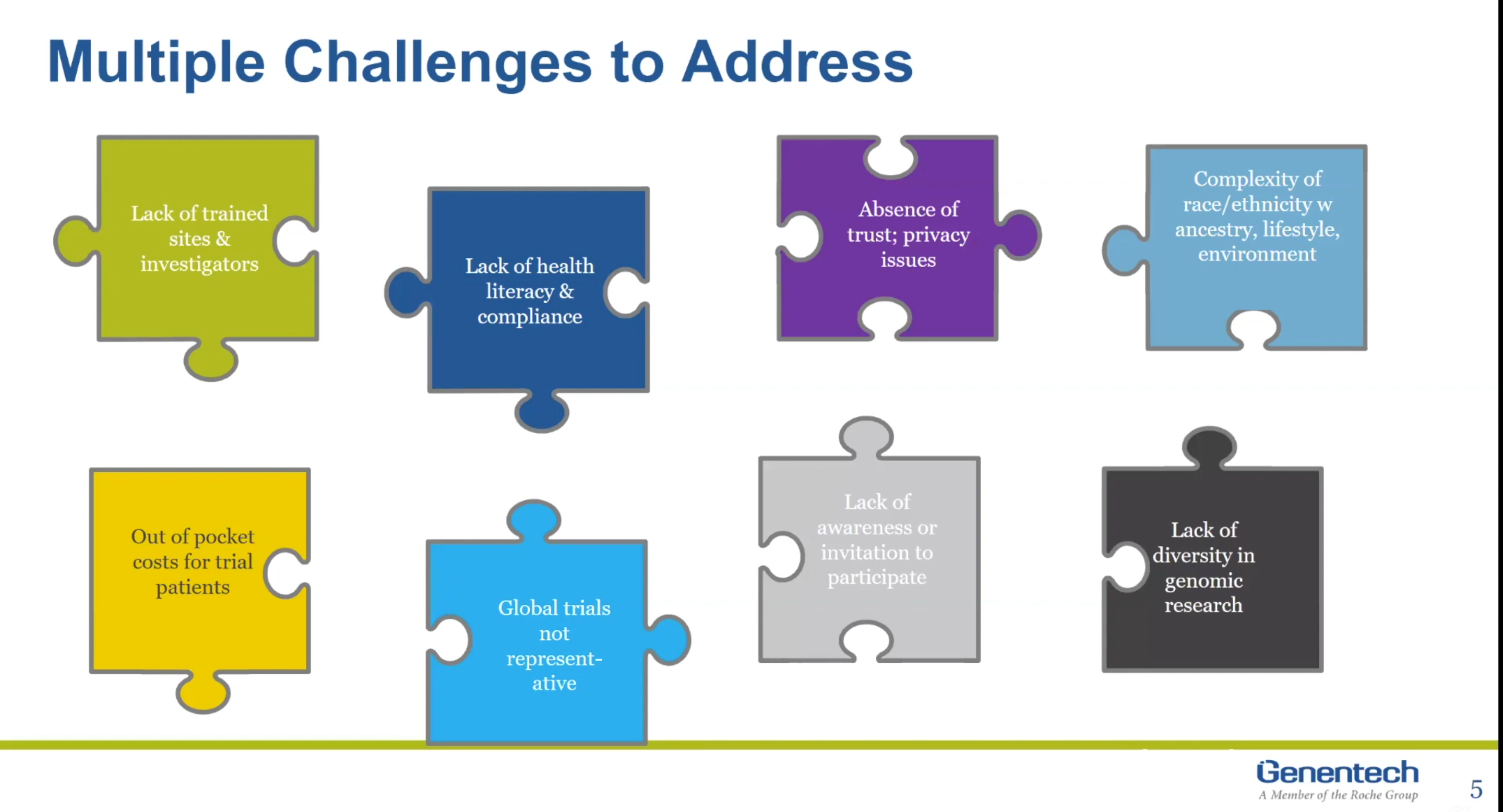

Alekhya Pochiraju: So, the diversity in clinical trials is a complex issue, has multitude of challenges and obtaining rights representation. I’ll try to go over few of these issues, and then deep dive on couple of challenges in my next upcoming slides. To begin with, there’s a lack of trained frontline staff that specializes in recruiting diverse population. And they have also seen there’s a correlation between patient and doctor diversity. Currently, both of these segments are not doing very well in representation.

Alekhya Pochiraju: Additionally, the consent that patients have to sign prior to participating in the trials can be hard to understand without the scientific background. We have an understanding you need to make it easier for our patients to understand our version of terms and conditions page. There’s room to improve on building trust and sharing more information on how data is generated from clinical trials and how that data, which is generated from clinical trials, will be utilized. One of the challenge that I have listed here is that race, lifestyle, environment, all of these are deeply intertwined and decoding it isn’t always straightforward. Additionally, assumptions and stereotypes and races also impact patient recruitment in the clinical trial process.

Alekhya Pochiraju: One of the major challenges is out-of-pocket cost. Since not all the costs are covered, it might be harder for patients to take time off from work and routinely visit hospitals for their treatment. We have also seen that the socioeconomic conditions are clustered to ethnicity and race. What I have on the slide is implying they are health deserts, which means that the nearest hospital for disease treatment isn’t really near. Additionally, we need more awareness, we need more education on clinical trials as a safe option. And as I alluded to my previous slide, genetic database isn’t really diverse enough to build on.

Alekhya Pochiraju: The intention of the slide is to highlight how global populations are changing. As you could see, the current population and demographic are not equally ported into the future. This emphasizes that lack of representation, if it continues to be unchecked, will lead to a larger problem of amplifying existing health inequities. This is a little crowded slide, so please bear with me. But, I’m trying to touch base here on few examples demonstrating the need for taking into account ethnicity and ancestry background, actual patient population, while designing trials. As you would see, for Lupus Nephritis, which is an autoimmune disease. And you can see a higher prevalence. However, the outcome of the current treatment is relatively poor, specifically for these racial and ethnic groups.

Alekhya Pochiraju: Similarly, lung cancer, it’s more commonly diagnosed cancer, and it’s also a leading cause of cancer death worldwide. There are higher incidents of specific mutations in lung cancer, that are related to racial and ethnic background. And this was identified because the clinical trial participants were diverse enough. I’m trying to get to, by saying that there’s a correlation between how a patient responds to a medicine and their racial and ethnic background. This exists in asthma, this exists in breast cancer, which I will get to the next slide. But, it exists in a lot of other diseases beyond what you see on the slide.

Alekhya Pochiraju: This is a stark, but also an unfortunate illustration. As you see, how black women have overall high mortality rates, about 41% due to breast cancer. But, they have very little participation in clinical trials. If you look at all the women of color cumulatively, there’s 80% of mortality, yet women of color constitute only 14% of enrollment in clinical trials.

Alekhya Pochiraju: A 2009 analysis revealed that 96% of participants in genomic-wide association studies, GWAS, what I will refer to as genomic database for our purpose, was based on European descent. So, 96% of the genomic database in 2009 was comprising of European ancestry. But since then, the progress has been made. In 2016, the analysis revealed that 81% of the information now is based on European descent. However, within minority population of that tie, African ancestry only accounts to 3%, and it’s much lower than Hispanic and Latin Americans. They only account to 1%. So, there’s still a long road to diversity.

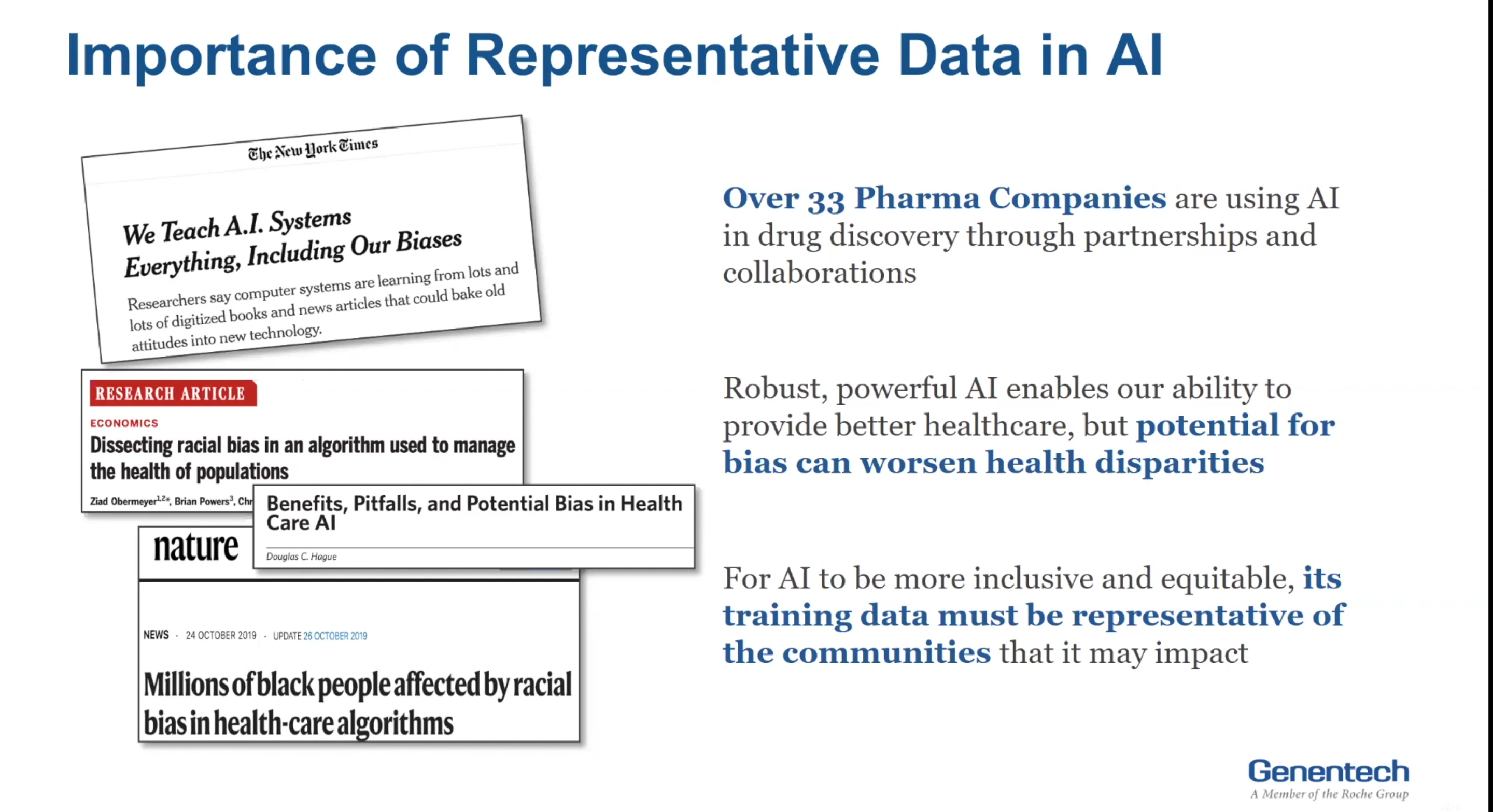

Alekhya Pochiraju: I heard that the audience that have dialed in today is predominantly from tech and health tech. So, I included a small blurb on artificial intelligence. So, AI is now widely used in discovering new medicines. And these AI abilities are built on existing systems that lack full representation. There’s rapidly growing concern, and also evidence, that new analyze technologies could exacerbate the bias in scientific discovery and clinical care. So, this is something to be mindful of, as the industry continues to leverage AI for drug discovery advancement.

Alekhya Pochiraju: Genentech developed the advancing inclusive research initiative, which is led by dedicated people. And their purpose is to understand the study challenges and also, to understand how to develop solutions, to ensure a proper representation of clinical trial participants. So this slide that you’re seeing here is heavily built on their work. While one of the primary challenges has been that site of care, as an example, would be hospitals, assume that minorities are not willing to participate. And a simple solution on the limitation for that, is to set expectations that all of the eligible patients are being asked. It’s also that the care giving sites, example again, hospitals, don’t always have staff that has experience in recruiting diverse population. And tech drug development companies can work with the site or the caregiving sites, like hospitals, to collectively improve this aspect.

Alekhya Pochiraju: Distance and finances can also be a huge deterrent, for which federally, or maybe privately, funding and support can be provided. The other takeaway that I had, is building trust and raising awareness and engaging minority communities that will help mitigate the participation gap. I want to conclude my presentation with this pictorial representation of what equality and equity looks like. Rather than equality, we should strive towards health equity With that, I can conclude my talk and I’m open for questions.

Sukrutha Bhadouria: Okay. Are we ready for some Q&A? Okay. So, we have some questions that came in and have been upvoted. So, what do you think contributes to the wide discrepancies in study subjects that you called out in your presentation?

Alekhya Pochiraju: Just give me a second. I’m having a little trouble here. Yeah. Can you still hear me, and could you repeat the question?

Sukrutha Bhadouria: Yes. What do you think contributes to the wide discrepancies in study subjects?

Alekhya Pochiraju: Yeah. Traditionally, minorities have not been participating. There’s many reasons along that. One of the primary … Or two of the primary things that I can think of, is fear. And the other aspect is the logistics. Sometimes it’s not easier to get to the hospital or the finances of taking part in the study, in the clinical study, because even after it being reimbursed, there’s a lot of out-of-pocket costs. And the fear could also be because a lot of times we have seen, in the past history, there have been clinical trials on the minorities, without taking their full consent. So, they don’t know what they’re signing up for. And then, the end of the trial, that is not what they had hoped for. So, that’s one of the two factors.

Sukrutha Bhadouria: What do you think about … Has there been any evidence where underrepresented groups would be more willing to participate if there’s some sort of compensation involved? So, as to increase the data set in underrepresented communities.

Alekhya Pochiraju: There have been studies. And one of the things that I would say, is the lung cancer study between the KRAS and the EGFR mutation. The reason why we knew that these mutations work differently in different ethnic groups is because the patients have been able to participate. So, there are plenty of examples, but there’s still a long road to go.

Sukrutha Bhadouria: Alright. Upvoting keeps changing and increasing. Okay. The next question. Are these studies just done in the United States, or are they across the world?

Alekhya Pochiraju: The ones that I had provided stats for, are global studies.

Sukrutha Bhadouria: So it’s a global problem that it’s not representative of actual fact. So, another person asked, am I wrong to extrapolate that without diverse test groups, prescribing medications to those groups not represented in trials puts them at a potentially greater risk?

Alekhya Pochiraju: Yeah. It is true because the outcome is not representative of the minorities that have taken part of this trial, because there’s only a small percentage of minorities that are taking part. So, we don’t know what the effects of the drug is going to be on this minority. There’s a clear correlation between the ethnic and racial background. And if these minorities don’t take part in the clinical trial, we just don’t know how the outcome is going to be for them because there’s not enough data to build on.

Sukrutha Bhadouria: Got it. Thank you so much. This was a great session and very insightful for all of us. Thank you.